The Ninety-Dollar Dress A TRUE STORY

From my as yet unpublished story collection, "THE ADULTERER'S DAUGHTER"

|

| My daughter Allegra, at 5, was all heart. |

MY DAUGHTER may be the joy of my life, but she

is clearly her father's child. She has his straight dark hair and hazelnut eyes. Her complexion, like his, is bronzer

in January than mine ever gets in July. Even her physique, beyond the obvious contrasts in anatomy and size, is

a miniature image of her dad's, from the soft, full-moon shape of her face to the funny curve of her second toe.

The resemblance, however, runs more than skin-deep. The two of them are as spontaneous and outgoing as I am deliberate and

shy. One of my daughter’s early teachers used to remark that Allegra was “all heart.” That heart is so light,

she often breaks into a skip when she walks. When alone, which is rare, she sings.

The odd thing is that when I was little, my mother says, I was just like her. Bursting with confidence, I babbled incessantly

to strangers on the street. I didn’t have a self-conscious cell in my body. Then something happened to make me clam

up. I reply to my mother that if there was

ever such a “something,” it wasn’t a single incident. It was my parents’ many years of unabated bickering.

It was the muffled sounds of malice emanating from behind their bedroom door. It was the icy contempt with which my father

glared at her almost any time she spoke. Still, the notion that something could happen

to dull my daughter's radiant eyes frightens me. How terrifying to think that I could make one thoughtless comment and turn

her into... me.

Of course, in my case, my mother didn't just utter one remark. There actually was a huge blunder I once made that she considered

unforgivable, and she harped on the matter incessantly. This episode happened decades ago, when I was just a small

child, yet even long after I grew up, she wouldn't let a month go by without dredging it up again. And each time she

did, I felt shame anew. In many families, particularly Jewish ones like mine, no statute of limitations exists on either inflicting

or feeling pain.

And so one day I dared to bring it up myself and discuss it, one adult with another. At the same time, I began to wonder:

Do I do anything comparable, quite unknowingly, to my own two children? I can’t believe I’m capable of such torment.

Neither do I imagine that the human spirit, especially that of my indefatigable daughter, is quite so easily crushed. But

my mother insists otherwise. She traces my reticence and my stultifying reserve to her own wrath and the ninety-dollar dress.

* * *

The story dates back to 1961. Our country was still swathed in innocence, and so was

I. JFK had just become president – still alive! – and I was no longer a wide-eyed 5. So my parents deemed me old

enough to attend my cousin David’s bar mitzvah. This bar mitzvah

wasn’t going to be your customary, run-of-the-mill affair, a Saturday morning religious service followed by a lavish

luncheon. It would be an entire weekend of feasting and celebration: a Saturday lunch, Sunday brunch, and evening ball straight

out of Gone With the Wind. For one thing, my cousin’s family lived down in Virginia. They’d be entertaining

countless out-of-town guests who, like my family in New York, would have to travel far. For another, Cousin David was Aunt

Gloria’s son. Nothing usual was good enough for them.

|

| Grandpa Charlie shunned "the family business," refusing to become a rabbi. |

|

| My mother, Bernice, and Gloria: Into a family of limited means, the Lichtenstein sisters were born. |

Gloria, my mother’s older sister and only sibling, had always demanded the best. Both girls had grown up in Brooklyn,

born to a struggling Jewish family of Russian immigrants in Borough Park. Their father, my Grandpa Charlie, was an erudite,

educated man who shunned “the family business.” He refused to become a rabbi like his father and brothers before

him. Instead, he questioned everything and read voraciously, indulging a passion for literature, science and philosophy. But

he was driven to study, not to succeed. After floundering in a series of unsuitable careers, he eked out a living selling

life insurance. This generated little income, but left plenty of time to sneak off to the library.

Into this household of limited means, my mother and aunt were born. It is said that wars

begin between adjacent countries when there aren’t enough resources to go around. So began a lifelong rivalry between

the Lichtenstein sisters. My mother, to this day, believes that

my aunt was favored overtly by their mother. There is no question that she was widely admired for her looks. Despite struggling

continuously with extra pounds, honey blonde Gloria was considered quite a beauty. My mother was far better known for her

brains, not exactly a priority for women in her day. My

aunt, as the family’s first-born child, was not only the first sibling to receive many privileges, but often the only

one. In those days, my mother explains, daughters were treated as second-class citizens. “The boy got everything and

the girl got nothing. Since we were two girls, and she was the eldest, she was treated like the boy.”

|

| Grandma favored fancy clothes,and her first-born child. |

|

| Honey blonde Aunt Gloria was considered quite a beauty. |

My Aunt Gloria attended Sunday school and learned to read and write Hebrew. My mother received no

formal religious training of any kind. My aunt was always dressed in exquisite, brand-new clothes. My mother didn’t

even get second dibs on these garments, since they were too roomy to fit her far scrawnier frame. My aunt was treated to summer

camp, and enriched by cultural lessons in everything from piano to elocution. My mother was permitted none of these advantages.

By the time her turn came around, there was never enough money left. "Once,” she recalls, “when she felt guilty, Grandma Mary took me down to the basement in our

building, where there was an old piano, and tried to teach me to play herself.” The experiment was never repeated, however.

My mother continued trying to “play by ear,” as she called it, picking out popular tunes herself, but never approached

the refined skills that her sister displayed at fancy recitals. To top things off, my aunt married young – before she hit 20 – to my Uncle Walter, a brilliant man of considerable

means. This was, perhaps, no coincidence. She had grown up poor, but with a taste for all things luxurious. Soon after, they

chose to move down South, to Newport News, Virginia, where money stretched like Silly Putty. Here, my aunt was finally able

to afford the finery for which she had always hankered. She set up house as an aristocrat, in a stately mansion teeming with

servants.

Her life, at least as we observed it, was one long and extravagant spending spree. When

she traveled by airplane, she sat in first class. When she visited New York, she booked a suite in the posh Waldorf-Astoria.

We could only imagine the luxury that was planned for the day her first-born became a man.

*

* *

My

mother harbored her own secret lust for grandeur, but had far from the means to indulge it. My father was still in his early

thirties and the fledgling stages of his career. We lived in a modest starter house in a working-class town on Long Island.

But like Cinderella, she longed to go to the ball wearing a dress with a fairy godmother label. To this day, she defends that lofty aspiration as a matter of family honor. It was something, she claims,

that she owed to my aunt. “She had invited her whole town. She had invited her whole temple. She was a very big wig,”

she explains. “And I, as my sister’s sister – her only sister – really had to look elegant.” Lacking fairy-tale connections, though, my mother had only one hope of attaining adequate style. She put me into our

bulbous, aquamarine Plymouth sedan and drove to Miracle Mile. Long before anyone had ever heard the word “mall,” this mammoth

shopping strip haunted the heart of fashion-conscious Long Island. Though perhaps not an actual mile in length, it was long

enough to encompass every store imaginable, from discount chains to specialty shops. Usually, we only gazed at the mannequins

in the windows of the ritzier stores. But this trip was different from all other trips. My mother took me firmly by the hand,

strode straight into B. Altman and up the escalator to Better Dresses.

|

| The dress resembled Audrey Hepburn's gown from "Breakfast at Tiffany's" |

|

| My mother, Bernice, was known more for her brains, not exactly a priority for women in her day. |

Within

minutes, we were escorted into a dressing room with an armful of slinky designs. I scrunched into a corner on the floor of

this cubby, my tiny fingers probing the carpet for stray straight pins while my mother squeezed her panty-girdled frame into

half a dozen chic prospects. Some were embroidered

with sequins or caviar beads, others trimmed with ruffles and lace. But the one that suited her best, by far, was a simple,

elegant, black velvet shift. This dress had no frills. It didn’t need them. Though lacking an actual designer pedigree,

it was eminently tasteful: a knock-off of The Little Black Dress, that soon-to-be classic that French couturier Hubert de

Givenchy had just created for Audrey Hepburn to wear in the movie Breakfast at Tiffany’s. My mother turned to face the mirror, then swiveled to check her profile. The dress fit her like a

black leather glove. She grinned at her svelte reflection, then grimaced when she surveyed the price tag. “Daddy’s going to love it,” I crooned as she straightened up and smoothed the shimmering

cloth over her hips.

“No, Daddy’s going to kill me,” she said with a sigh. “Ninety

dollars! It’s much too much.” For most people in today’s economy,

that figure would not be a splurge, especially for a special occasion. Ninety bucks then, however, was a very different story.

Spending so much on a single dress was hardly within the realm of a middle-class budget. My mother maintains that my father could have afforded to let her buy it anyway. He simply wouldn’t have wanted

to. “He was doing pretty well,” she says. “He just wasn’t a spender yet.” There was no way on

earth that he would have allowed such a purchase. If he knew about it, that is. And so it was that, inside this compact dressing room, my mother hatched a plan. Actually, it wasn’t much of a

plan. The plan was that she would buy the dress, but under no circumstances let my father find out how much it cost. This, luckily for her, was long before the popularity of credit cards. My father would receive no

tattletale bill from MasterCard or American Express. My mother had gone on this shopping expedition armed with actual cash.

Only she would know how much she’d plunked down for a measly few yards of cloth. There was only one potential flaw in this scheme: She had already told me how much it cost. She had to make sure I didn’t

squeal.

All the way home in the car, we rehearsed what I would say. It was a dramatic role that

even a 6-year-old could handle. After all, it involved no lines. I was to say absolutely nothing. “Not one word,” my mother repeated at home as she prepared dinner. “Do you understand?”

She was counting on me. What my father didn’t know wouldn’t hurt him. We would keep our entire shopping trip a

secret.

Even at 6, I knew about secrets. I had simply never possessed such a juicy one before.

“Don’t tell Daddy,” my mother had ordered. I rolled the words around on my tongue, savoring a flavor far

sweeter than any Sugar Daddy, Tootsie Roll or other candy I’d ever eaten. I knew something my own father didn’t

know. It was my first taste of trust and true power.

|

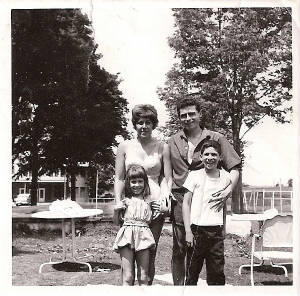

| My family on vacation later that year, in August of 1961. |

The thrill of being caught in such intrigue was almost more than I could bear. I was privy to classified information about

which my older brother, a worldly and superior 8, hadn’t the slightest inkling. While he sat upstairs, a slave to ignorance

and the rigors of third-grade homework, I took up my usual evening post peering out the front door. Watching for my father

to return from work, I practiced silence, my head resounding with all the words I had promised not to say. My father, unlike my

mother’s father, was a deeply ambitious man. He valued hard work almost as much as its intended result, material gain.

Commuting to and from New York City each day, he worked long hours as a salesman at a firm that he would eventually buy. On

good nights, he returned home late from the office. On bad nights, he came home very late. This, it turned out, was

not a particularly good night. I had a long time to wait and think.

By the time his black Thunderbird had rounded the corner, an eternity had passed. Slowly,

carefully, my father pulled into our driveway. He inched down the blacktop at a leisurely pace, then let his car idle in neutral

while he stepped out and bent to lift the heavy garage door. Then he returned to the car, stepped back inside, and let the

T-bird glide into the one-car garage attached to our house by a breezeway. I listened as he paused momentarily, perhaps catching

the end of a report on the radio before shutting the engine. By the time he had slammed the car door shut, pulled down the

garage door and ambled up the walk to our house, I was ready to burst with the words.

|

| The second dress, low-cut and flashy, made my mother feel cheap. |

When he opened

the front door, I did.

“Guess what Mommy did today." “What?" “Mommy bought a ninety-dollar dress!" “WHAT?” By the time my mother had dashed out from the kitchen, it was already too late. * * *

He looked at the dress, but wasn’t impressed. It went back the very next day. To replace it, my mother was put on a very strict budget. She could spend up to $45, tops – no more than half

as much.

With such restraints, she didn’t dare venture into Altman’s. She was reduced

to shopping in the lowly, bargain-rate Alexander’s. The best she could find there was a tight black sheath with a low-cut,

ruffled neckline. Though somewhat similar in cut to the first dress, it was the opposite of refined. It was flashy. “It

enhanced my figure,” she recalls, “but it wasn’t the proper dress to wear. I didn’t feel elegant in

it. I felt cheap."

|

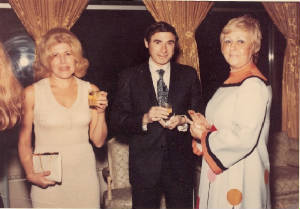

| My mother, father and Gloria at a party some years later, in 1973. |

My Cousin David’s bar mitzvah turned out, indeed, to be an affair to remember. Being only 6, I was sent to bed early

on Saturday evening, long before the dancing began. But my mother remembers that at the party, a man at my parents’

table admired her dress, noting that she reminded him of Paris. My father laughed, she recalls, and remarked, “Yes,

the Left Bank.” She is convinced that this was a reference to the French prostitutes who congregated alongside the Seine

to ply their wares. She felt utterly mortified. I cringe now thinking of the

humiliation she suffered because of my loose young lips. I sorely wish she had gotten her chance to measure up at last, after

decades of being overshadowed by her own ever-superior sibling. Instead, she was the poor relation, shown up once again.

Her anguish, however, lasted for only one night of a weekend long forgotten by everyone else.

My punishment endures to this day.

From the moment I blurted out my mother’s little secret, I was branded for life.

Never would she dare to confide in me again. I was untrustworthy. A stool pigeon.

Nothing I could do would convince her otherwise. A few years later, when I was 9, I was

visiting a friend when the girl’s mother accidentally ran over her little brother in their driveway. While we waited

for the ambulance, the frantic woman ordered me not to tell anyone. And I didn’t. My mother was shocked when news of

the incident finally reached her days later. What astounded her most was that I’d witnessed the whole thing and hadn’t

breathed a word to her. Yet she still told everyone not to trust me.

The problem was that my family life was riddled with secrets. Not just silly secrets

about overpriced dresses, but dark, dirty ones. Most of these related to my parents’ troubled marriage. And most of

them were secrets that, despite their best efforts, I knew.

* *

*

Although there must have been some moments of relative calm during

the 29 years that they remained legally bound, I can’t recall one when they were visibly content. My earliest memory

of any kind dates back to when I was 4. I’m sitting in the hallway outside their bedroom, listening to them talk. Their

voices aren’t raised, for once. The conversation, in a distinctly minor key, is conducted sotto voce. Yet I can easily

make out what they’re saying. My father says he doesn’t love her any more. My mother says almost nothing. All

I hear from her are muffled sobs. The mind plays tricks on us all, of course; it’s perfectly possible that I have mixed this discourse

up with other exchanges very much like it that I overheard over the years. But about the next part, I am certain. Suddenly,

the door to their room flies open and my mother is running toward me. As she passes, she hoists me into her arms, and half-pulls,

half carries me down the stairs and outside. Now we are sprinting across the front lawn, my father charging after us in hot

pursuit. Just as we reach her car, which is parked out front alongside the curb, he catches up at last and tries to rip me

from her grasp. My mother won’t let go, however. Never a quitter, she clutches me by one arm. My father latches onto the other. Then

they proceed to have a tug of war, using me as the rope.

“Let go of her!” my mother shrieks at him. “Stop it! You’re hurting

the child!” She doesn’t refer to me by name. I am an object. I am the child. Her frantic warning works, however.

He releases me instantly, and my mother and I clamber into the car. She fumbles with the key, then jams it into the ignition

and pumps the gas. I look back as we race down the block. My father is still standing there watching, his face as red as raw

meat. I don’t make a sound until we reach the first stoplight. Then I begin to cry. “What’s the matter?”

my mother demands. I don’t answer. I try to stop, but can’t.

By the time that my father left, though, many years later, I could control myself. Perfectly.

At least, I didn’t dare cry.

* * *

|

| When I was 17... NOT a very good year. |

Throughout my adolescence, my father repeatedly left my mother, moving in

and out of our house to go live with his mistress in the city, often for months at a time. I knew where he was, and whom he

was with, because he took little care to disguise his behavior. I knew because my mother, having no one else to confide in,

discussed it with me regularly. Discussed it in excruciating detail. My mother, though, remained convinced that my father

would eventually settle down from what she called his “mid-life crisis.” For that reason, she didn’t want

other people to know what was happening in our house. I was forbidden to tell anyone – even my closest friends. And

I didn’t for almost a decade. The hardest test came when I was 17 and my parents separated for nearly a year. They hadn’t

yet decided whether to actually divorce, though, and didn’t want anyone to know of their rift – not even my own

brother. He had just returned to school

for his sophomore year at a state university, and they feared that this news would shatter him. The problem was that he was

dating one of my friends, a hometown girl, and he journeyed home almost every weekend. To avoid distressing him with the harrowing

truth, we engaged in an elaborate charade.

|

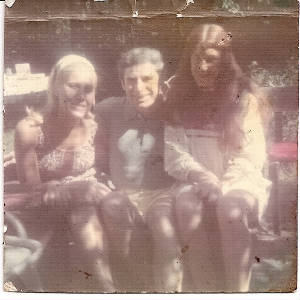

| My brother, a college sophomore, was not to know my parents were separated. |

On Friday evenings, shortly before my brother arrived, my father would return from the

city and quickly unpack his suitcase. After my brother departed on Sunday night, my father would pack and leave again. I was

sworn to secrecy and didn’t divulge this peculiar arrangement to my sibling until years later, after they had finally

divorced. My sadness about this sick situation,

though, and the relentless pressure to keep it a secret, grew so unbearable that year that one afternoon, I truly could stand

it no longer. Overwrought and unable to think clearly, I removed the inner screen from one of the windows in my bedroom, pulled

out all the glass jalousie slats and crawled outside. And there I hung, head in, body out, clutching the window frame while

I tried to decide what to do. It didn’t cross my mind that my room was only on the second floor, and that falling would

probably just break my legs or back. I had little doubt that the impact of a fall would hurt like hell, but I didn’t

really care. I just wanted the inner pain to stop. I

hung there that way for about ten minutes, letting my body slip lower and lower, until I realized that I was about to lose

my grip and fall. I must have cried out then, because my mother suddenly appeared in my bedroom, screamed, and pulled me in.

Then, shocked with outrage, she actually spanked me. Whether or not it was her preference

or mine, I never told anyone about that day. The result is that I grew up to be something

of a professional confidante. Friends and relatives call me daily to divulge their heartbreaks and other troubles. I think

their eagerness to seek my counsel stems largely from the fact that I’m a sympathetic listener. The main reason I think people confide in me, though, is that they sense that they can truly trust me. If they reveal

something private and potentially embarrassing, it’s like putting that information into a vault. Having learned my lesson

the hard way, I like to imagine that I’d actually stand up well to torture. There are even secrets I know that might devastate my mother. But she needn’t worry. I’ll never tell. Thanks

to the ninety-dollar dress, I learned my lesson well.

* * *

It was only

when I became a parent myself that I began to realize that my one unfortunate confession wasn’t really my fault. I started

conducting occasional, informal experiments with my own children. I wanted to prove to my mother that I had merely done what

any 6-year-old would do. But mostly, I wanted to prove this to myself. In one such instance, when my daughter was 6, she begged to know what I’d bought her older brother for his birthday.

Plaintively, she pleaded for me to whisper it in her ear. Having poignant memories, I murmured an answer that was false. Yet

that’s not the only reason I sighed with relief when she blurted out the news to my son instantly.

|

| Aunt Gloria, always the first at everything, also, sadly, died long before her time. |

More recently,

I’ve begun to think about what the dress incident meant to my mother. It wasn’t about needing to impress other

people. It wasn’t about fashion, or foolish pride. It was that, for once, I think, she wanted her own mother to love

her as much as she seemed to love her sister. She didn’t dare hope to be the favored child. She just wanted to appear

equal. More important, she wanted to feel worthy of such love. If so, then she finally got what she

desired, although – isn’t it always the case? – not as she ever would have wished it. For my poor Aunt Gloria,

always the first at everything, died long before her time, too. She passed away in her early sixties, after an agonizing battle

with breast cancer.

Meanwhile, my grandmother continued to live on and on. Dear Grandpa Charlie had passed away nearly nine years earlier. Only

my mother remained to be Grandma’s family and tend to her many needs. And tend to them she did. Although Grandma Mary had long ago moved to Florida, my mother took over her affairs. It wasn’t

merely a matter of seeing that the bills got paid. She flew down often to pay Grandma extended visits. She hired a succession

of women to care for her when she wasn’t there, yet still made sure to telephone her five or six times a day. When Grandma approached 90, my mother moved her to a fancy retirement home. But she took care to make her quarters there

look the way her old apartment had: filled with family photos, with a larger-than-life-size portrait of my aunt, painted in

her glory days, gazing down regally from over the living room couch.

|

| With my mother and Allegra before Allegra's senior prom. |

|

| Grandma looked great at 43, in 1947. |

It was here that

my mother, who worked as a teacher, spent school vacations, most major holidays and at least a month each summer. She carted

her mother to doctors, administered her medications and read to her aloud. She was so busy with Grandma that she rarely got

to see her own children or grandchildren. It nearly consumed her life. My grandmother just seemed to expect it all. Then, one afternoon, something changed. Grandma woke up from a nap, saw my mother there and seemed

startled. “I dreamt that Gloria was here,”

she said, talking as though still in a dream. “She drove me to a store, and then we came home and she went to find my

shoes. But it wasn’t her, was it?” Grandma asked. “You’re the one. It was you all along."

|

| My mother wore a gorgeous dress to Allegra's bat mitzvah. |

|

| With Grandma, nearly 98, just before she died in 2002. |

Ever the pragmatist, I took this at face value. Grandma had simply had a dream about my aunt. But in her words of sudden

recognition, my mother gleaned much more. “She knows!” my mother exclaimed

to me. “Everything I’ve been doing for her all this time? She finally realized it wasn’t my sister. It was

me.” In this light, the load she’d

been carrying for so many years suddenly looked less like a burden than a privilege. “I love Grandma!” my mother

declared in the same breath. “I hope she lives forever.” If only it could be.

Meanwhile, I should know better than to give

away any secrets. But if she can forgive her mother after all those years, then surely I can forgive mine.♦

|