|

Friday, August 28, 2015

A Word From the Weiss  There are five words I say every year at around this time:

Where did the time go? Between

my summer job and all the hoopla surrounding our son’s engagement – not to mention our daughter’s

return to the family fold after a year away in Hong Kong – my husband and I had no time to plan a summer vacation

this year, let alone take one. So there we were suddenly, in the skin-scorching throes of August, with back-to-school commercials blaring round-the-clock. A summer

getaway was a matter of now or never. I chose now.  It seemed foolish under the circumstances to attempt anything

terribly ambitious. And by “ambitious,” I

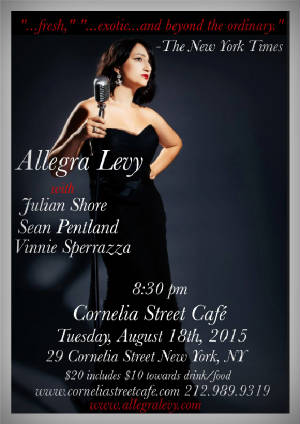

mean anything involving a plane, passport, or alternate time zone. No matter. As it happened, our daughter Allegra was scheduled to sing at a trendy club in NYC on the night of Tuesday, August 18th, and of course we wanted to be there.  As luck would have it, the weekend leading up to it coincided

with the opening of the 19th annual New York International Fringe Festival, a two-week extravaganza featuring theater,

dance, comedy, improv, and the like – over 1,100 performances in all. We decided to spend the few days prior to Allegra's gig in NYC enjoying

a few of these. Then we would hit the beach on tranquil Shelter Island off the North Fork of Long Island. Summer in the city. Then fun in the sun. Who needed Paris, Bali or Machu Picchu? Last minute or not, near or far, it sounded like a summer vacation to me.  Once upon a time – OK, actually, it was twice – we attended the granddaddy of all international fringe festivals by flying all the way to Edinburgh, Scotland. The first time we went was to attend a wedding. The second time was because ever since the first

time, our daughter’s ultimate ambition

had been to perform there as a singer someday. As a theater buff,

I can imagine almost nothing more appealing than attending a smorgasbord of lively dramatic

and comedic performances night and day. That’s what we did the first time around. The second time, we

went along with Allegra and her band, mostly because

she was only 18 at the time, and as a nice Jewish mom I couldn’t imagine letting her travel to a distant land with four young men I didn’t know.  We put her and her rather motley crew up in an apartment with us for an entire week. The band turned out to be very nice young men, after all. Then again, after performing each evening, they

would stay out drinking all night, then come home, trash the place, and sleep all day. Happy as we were to help support our daughter’s budding musical career, my husband and I soon realized that we were not cut out

for the rock star’s life, let alone

that of a jazz musician. And as much as we loved the hip, edgy Edinburgh Fringe festival vibe, I left with such a bad case of PTFD (Post Traumatic

Fringe Disorder) that I was inclined to never go back.

But attending a similarly cool event in nearby NYC seemed much more manageable, to say the least.  Most of the New York performances were held in assorted theaters

in and around the East Village. The first

one we attended was a lively musical rom-com called #LoveStory. I chose this one because we were attending it with our

own member of the Hashtag Generation, Allegra. “In the digital age, finding

love should be as easy as sushi delivery, right?” the synopsis read. It turned out to be about a 25-year-old named Zoe looking for love online and elsewhere in NYC. Never mind that our own 25-year-old

New Yorker has already found love in Hong Kong,

and was simply waiting breathlessly for Mr. Hong Kong to join her in NYC next month. The way she howled through the whole production made

it clear that this off-off Broadway musical was not only a hit, but had clearly hit a chord.  As with almost any Fringe festival, selecting what to see is largely a matter of hit or

miss. And for me, the title alone is often enough to make me err on the side of caution and choose to definitely miss. Such was the case with a B-movie send-up called She-Rantulas from Outer Space in 3-D, a comedy about an alien invasion

in 1957, as well as another called An Inconvenient Poop. “What if the solution to climate change, world peace, and self-love was something no one wanted

to talk about?” the latter asked.

Or wanted to see.  But we dared to try our luck with a play called – I kid you not – I Want to Kill Lena Dunham (a sentiment I decidedly

do not share). It turned out to be a thought-provoking dramatized diatribe about a black young protagonist named Nora who

is frustrated that Ms. Dunham does not use her influence as the supposed Voice of Her Generation to tackle issues more substantive than the petty,

bourgeois travails of the quartet of 20-somethings on her HBO series Girls.

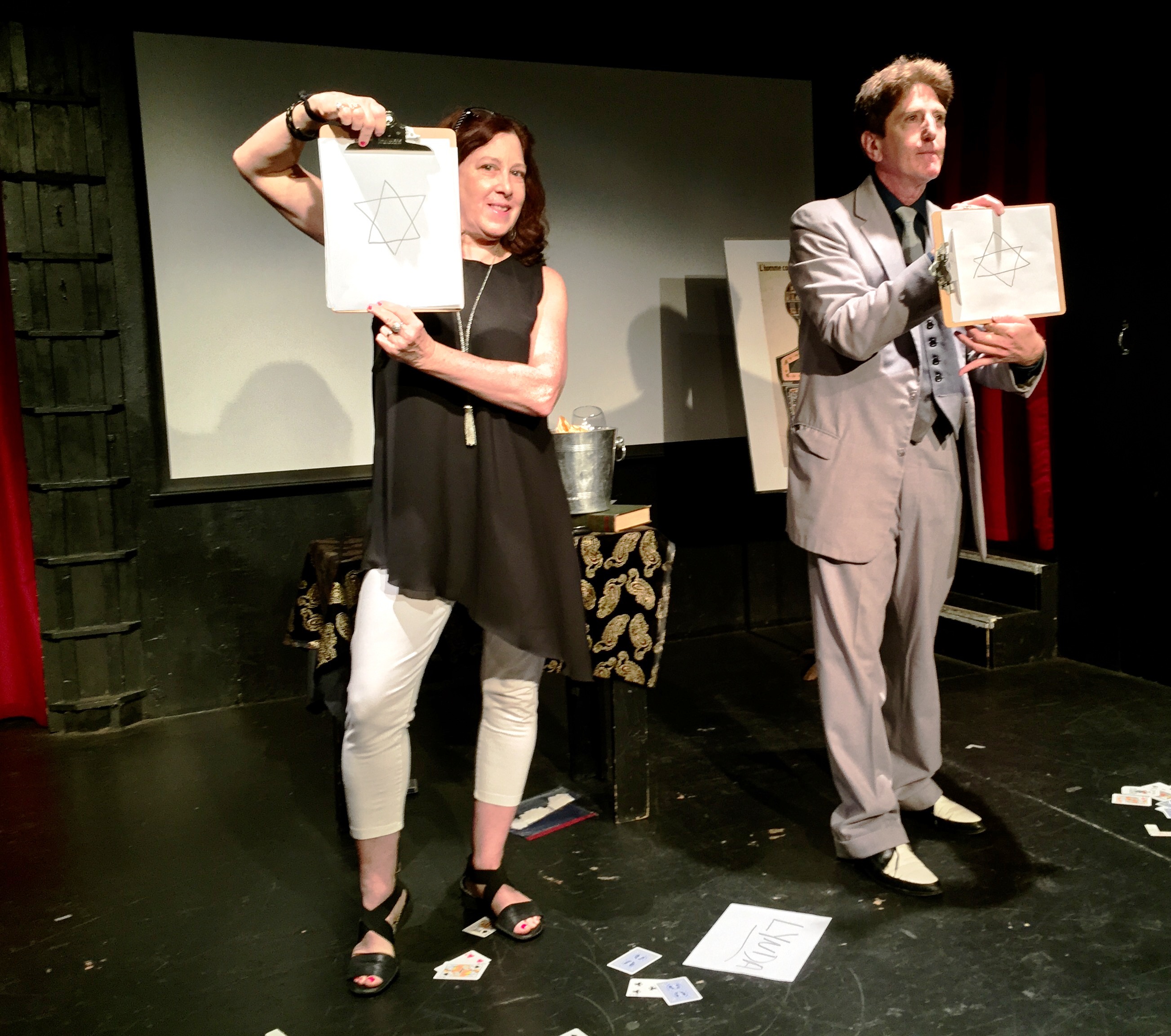

My husband’s favorite Fringe show, though, was one in which I actually got

to participate. In recent years, we have begun to gravitate toward sitting

as close to the stage as possible, due to problems he has with his hearing. But when it came to seeing a mentalist’s show, we should have known better than to plant ourselves right in the front row.  Sebastian Boswell III, a self-styled clairvoyant who won “Best of Fringe” at the 2014 San Francisco Fringe, billed his one-man show This Side of the Impossible. For his opening act, he performed a novel card trick in which he managed to more or less memorize an entire deck of cards in 20 seconds – 13 seconds flat, in fact – with my husband selected to serve as the time keeper. He followed this up with a trio of mind-reading stunts. He asked a man in the audience to think of

the name of a friend he hadn’t seen in awhile, then write down that person’s

name on a slip of paper and seal it in an envelope. A girl in the back was recruited

to do the same with the name of a family pet. Then he suddenly summoned me. My role was to draw a simple design that I would be able to reproduce,

and seal it in an envelope as well. Then I was

invited to join Boswell onstage and stand with my back to him while I drew my design

again. Facing the opposite way, he would draw it as well.  The results? He guessed correctly that the man he had chosen from the audience was thinking of his friend Linda. The girl, he also somehow knew, was thinking of her

dog Archie. Yet how could

he tell what I had drawn? Was it a matter of smoke and mirrors? Had he studied the movement of my hand as I sketched? Or did he somehow intuit that I was NiceJewishMom.com and I was almost guaranteed to draw a Star of David? Whatever

the case, my husband is still talking about it. But all that I can talk about are the absolute highlights of our entire vacation: our daughter’s gig at the Cornelia Street Café

and my shopping excursion with our son’s bride-to-be

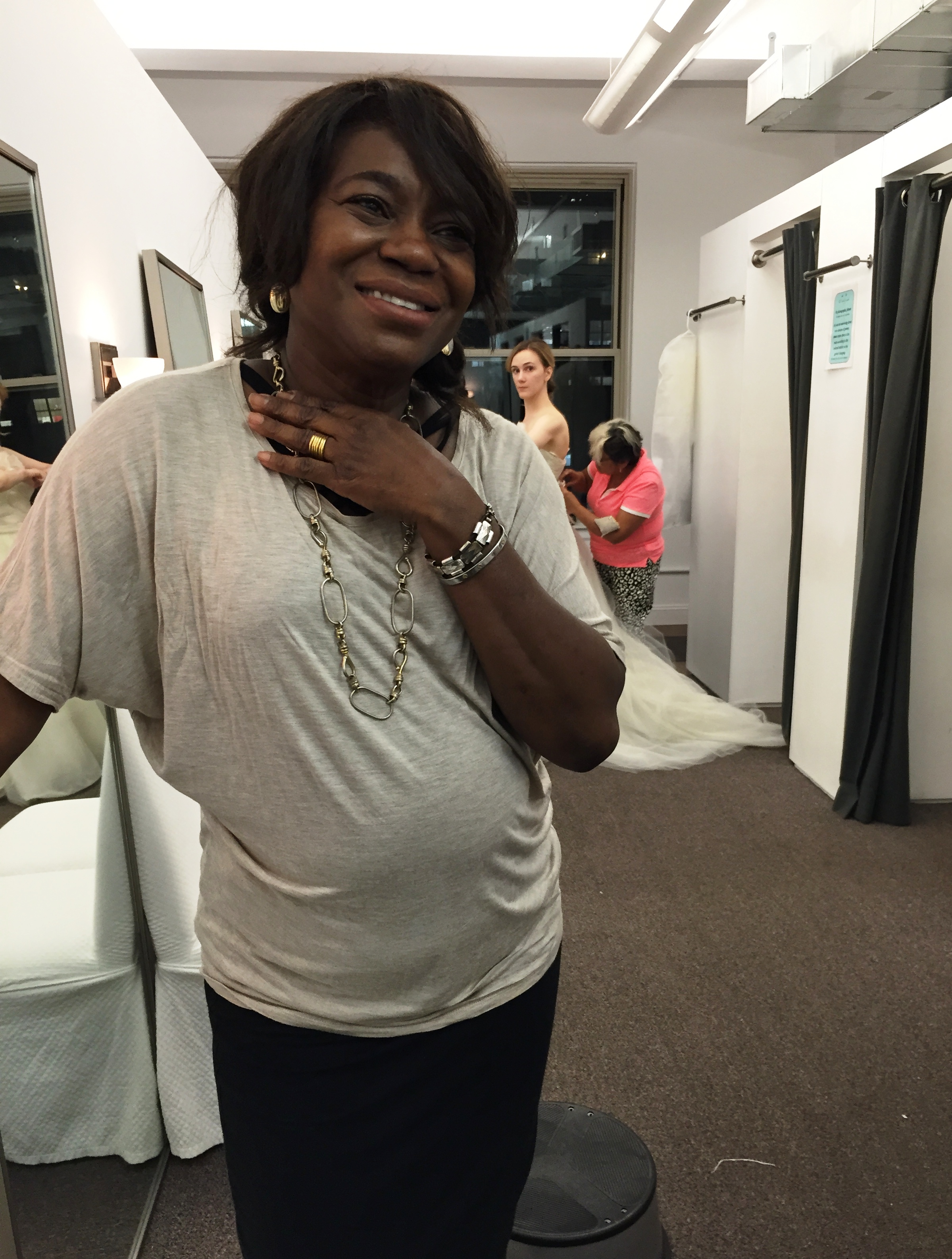

for her wedding gown. Last things first.  After a preliminary trip with the bride, Kaitlin, to David’s Bridal, a national chain with more than 300 stores in 45 states, Allegra, who is one of Kaitlin’s two co-maids of honor, decided to seek out a place

to buy a gown that might be more affordable and also less generic. That’s when she

discovered The Bridal Garden.  The only not-for-profit bridal boutique in

NYC, this novel shop, located on 21st Street off Sixth Avenue, sells brand-new wedding gowns donated by prominent designers including Vera Wang, Oscar de la Renta, Marchesa, and Badgley-Mischka – as well as gently used ones from private individuals – for up to 75

percent off the original price. Most of these gowns are high-end. Many are one-of-a-kind. Best of all, 100 percent of the profits go to a charitable

cause. The shop has helped thousands of children and their families since its inception in 1997. It currently

funds the Brooklyn Charter School, an elementary school in Bedford-Stuyvesant that emphasizes literacy and the arts.  It’s necessary to make an appointment in advance

to shop there – a week ahead

is recommended for weekdays and as much as three weeks for weekends – and because the boutique is relatively small, you are only allowed to bring two

people along with you. When Kaitlin chose me to

be one of her two, I felt like I had won the lottery.

We met inside the store, located on the ninth floor of a building on

21st Street. Inside, we discovered racks teaming with gowns arranged by size. Almost every size there is.  Brides, after all, also come in every shape and size, and several were already busy there modeling prospective

nuptual fashions for their own admiring entourages. While we

waited for Allegra to arrive from a rehearsal, Kaitlin and I each chose an armful of dresses, which

we lugged with great effort to her designated

dressing room. (The weightiness of

the notion of having a wedding itself is somehow outdone by the heft of all that cloth and heavy beading. Some gowns aren’t just worth

their weight in gold. They weigh almost as much as gold.)  Even though I had little to do but help zip up and then ooh and ahh, I grew utterly exhausted in no time flat. Good thing

that Ashley, an affable assistant manager, was nice enough to re-hang many of the chiffon and lace behemoths when we were done. And soon enough, Allegra

arrived and took over my zipping duties (although

I continued to sit close by and ooh, as well as ahh). She also collected her own armful of frilly

selections. One was a strapless Vera Wang gown with Art-Deco-style rhinestone beading and drop pearls along the top and an ethereal skirt of

champagne-hued tulle. OMG! Kaitlin looked so gorgeous in it that we all agreed it might be The One.  But just to be sure, she slipped on yet another dress, also strapless, but with a sweetheart neckline and floral lace the bodice. This one, from

the Bridal Garden’s own private label, was not only lily white, but so

traditional that the moment Kaitlin added a veil, the deep profundity

of the circumstances hit me. My son was really getting married – married to this wonderful girl. And I began to cry. “If you’re getting this worked up

already, how will you survive on the actual day?” asked Ashley, the assistant manager, with a grin. Heavy drugs? Hypnosis? At the very

least, waterproof mascara.

But that was a whole year away. There was a more immediate question at hand. Dress

No. 1? Or No. 2?  While I sheepishly dried my eyes, Kaitlin slipped the previous

number back on, and from the radiant flush of joy that illuminated her face, brighter than any midsummer sun, I knew.

We had indeed won the lottery!

“You can’t go wrong with Vera Wang,” noted Vivienne, The Bridal Garden's eminently knowledgeable consultant and seamstress. It seems like it would be crass for me to

talk specifics about cost here. Let’s just say that the original price was well

into the thousands. And the price we paid was not.  “We sell everything at a discount – deep discount, as they say,” Vivienne observed. Fortunately,

that also applied to the exquisite fingertip-length veil we found in the exact same shade of champagne tulle. Since it was by Toni Federici, evidently a top veil designer, the original price was $750, but we ended up paying less than a third of that. Who knew wedding veils were that expensive? Not

me. Till now. Bargain or not, the

most exciting thing was that 10 months

before the Big Day, our search was already over.  “We said yes to the dress!” Kaitlin exuberantly posted on Facebook. And

I didn’t hesitate to say yes to celebrating with champagne.  Although little in my lifetime will probably ever top that, it was still a thrill as always

to attend Allegra’s performance at the Cornelia Street Café the

following night. Aidan and Kaitlin, along with Kaitlin’s always-genial Uncle Joey, met us for dinner, followed by the

show. Allegra had hired a phenomenal band, and if you ask me, she killed onstage and looked too darn hot in the fab new striped dress we’d found at a trendy boutique in the Village.   The next morning, it was time to pack up. The city

segment of our trip was over. Time to head to the beach!

Years ago, we had taken a series of ferries from Connecticut to Sag Harbor in the Hamptons that required us to drive

across Shelter Island. Each time, the island looked so scenic that I wondered why we were only driving through. This year,

we chose to stay.

But stay where? I took one look at the appealing photos posted online of a boutique hotel called The Shelter Island House and knew instantly that this was the kind of style and elegance I craved for the beach part of our last-gasp-of-summer getaway. Yet I am happy to report that this posh haven

still managed to exceed our great expectations.  No wonder TripAdvisor rated it No. 1 among the accommodations on the island. The recently renovated rooms were fresh, pristine and spacious. Although the beaches on Shelter Island are relatively small,

one of them, Crescent Beach, was barely a five-minute walk away from the

inn and an even quicker drive. And after

we returned before dusk each day, my husband and I found that we always had the pool out back to ourselves.  The house-made

multigrain and chocolate croissants at breakfast were to die

for… as were the avocado fries (more like

avocado tempura) on the dinner menu, half-price daily (along with a tempting selection of BOGO cocktails) at Happy Hour from

4 to 7.  The on-site restaurant also offered phenomenal food and weekly specials, such as prime rib with mashed potatoes

and salad for $25 every Thursday (featuring a mammoth slab of meat so large that we wished that we had shared). There are plenty of other restaurants on the island, including the eminently popular Vine Street

Café, which we felt obliged to try one night, just for a change.   But the truth was that we were so content at the inn that we were inclined to just stay put. It was a pleasure to dine there each night, then merely walk

down the hall and tumble blissfully into a plush and comfy king-sized bed. The staff was also

warm and welcoming. Good thing we didn’t just drive across this year. It was worth every

penny. We’ll be back! As for Shelter Island itself, we discovered an unexpected and

unfortunate truth. My impression from driving through all those years ago was that it was low-key and unpretentious, a land that time forgot. With nearly a third of its well-preserved

and rural 8,000 acres owned by the Nature Conservancy, it seemed like the opposite of the Hamptons,

which exude a glaring air of conspicuous

consumption.  All it took was to wander into a few of the shops in the nearest town, though. From the trendy clothes to the fancy food, nearly everything was exorbitantly priced. No deep discounts

here. You might call it inconspicuous consumption. It may be a land that time forgot, but don’t forget your American

Express card, Visa or MasterCard if you go.  We spent our final

night visiting our old friends Arthur and Sari in East Hampton. Never mind that Arthur

is the cardiologist who created the famous South Beach Diet. Our time there turned out to be largely about consumption, period. Even if everything we ate was notably healthy, Sari is

such a balabusta (incredible cook) that I fear I put on 4 pounds.  But now, alas, we have

bid both the city and sea good-bye. It’s nice to be home. There’s

no place like it, as they say. But I'm back to saying those five little words.

Where did the time go?

Friday, August 14, 2015

A

Word From The Weiss (Last week, I wrote about preparing

for my summer job. Here’s how it went.)  I woke up early the next morning and put on the uncharacteristically

conservative new outfit that I had been saving for this very day all summer – a black sleeveless knit top and dark tailored slacks with a knife-sharp crease still down the center of the leg. I tied on a tasteful floral scarf in muted tones

to inject just a hint of color and personality. Then I stepped back to survey the

person that I was about to become in the mirror. “Look, Mom!

I’m a teacher,” I said. My mother, who had left this earth some six years ago,

had been an educator all of her adult life. I figured that she had been waiting for this moment to come all of her life. Maybe all of her death, as well. Wherever

she was now, I knew she would be proud.  I lifted my salmon-colored satchel brimming with printed materials to hand out, along with the generous collection of snacks I had

assembled for my students. When I had told my daughter that I was buying candy and granola

bars for my classes, she had snorted, reminding me that they were college kids, not middle-schoolers or tiny tots. I had simply snorted back. As a nice Jewish mom, I knew something about kids of every age. From babyhood through Bachelor’s degree

and beyond, they were always hungry. Time to

go! Just before exiting the house, though, I had a sudden inspiration and dashed back

upstairs to my daughter’s room to borrow a special prop. What would she care? She was

now grown and living on her own. Maybe I would

confess later. Maybe not.  The labyrinth of hallways at the gargantuan University

of Connecticut Health Center was so vast and

convoluted that when I had driven there the previous week. I’d had to practice repeatedly finding the downstairs office that would serve as my home base for the coming weeks. I didn’t

dare risk getting lost in this maze on the actual day. Now Jan, the friendly and ultra-efficient administrative assistant, took one look at my arsenal of junk food and laughed. “The kids are going to love you!” she exclaimed. I guess I had guessed right. Jan ushered me down the hall, up a staircase, and then through

another series of hallways to a classroom that I feared

I would never be able to find again. Yikes!

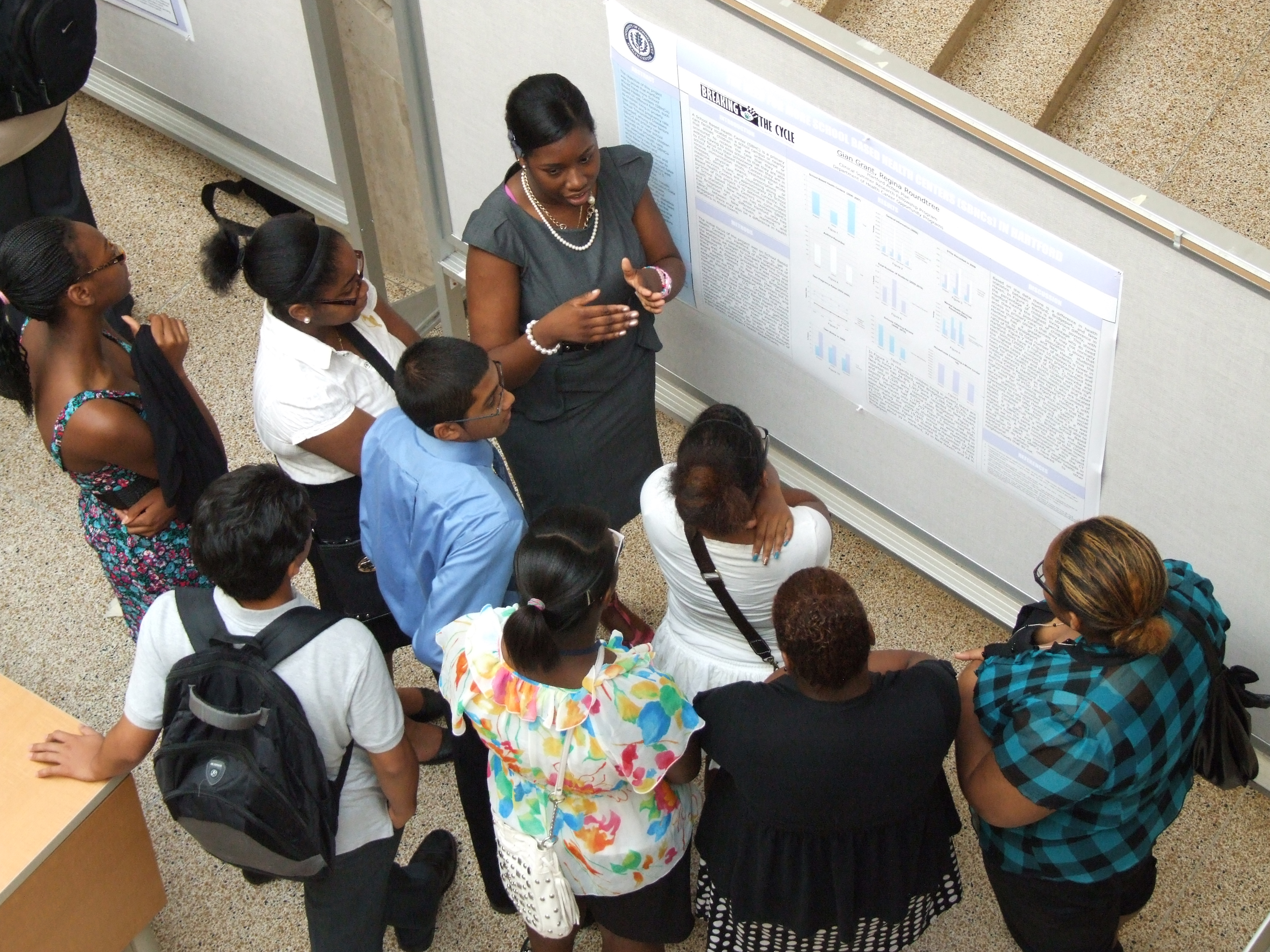

UConn’s Health Career Opportunity

Programs had been created to help young people from diverse backgrounds underrepresented in the health-care field get

into medical and dental schools. I had been hired

to help the participants write the personal statements for their school applications. My first class consisted of 10 aspiring

dentists who were already seated in the room, where another instructor had just finished up.  I set up a pair of bowls filled with mini-bags of M&Ms and other sweet snacks beside my stacks of printed handouts

and invited everyone to come take one of each.

“Look, candy!” someone cried. I didn’t need

to ask twice. I guess I had guessed right. When

I had practiced my lecture the night before for a kind neighbor who'd offered to serve as my academic guinea pig, I had done

it seated comfortably on her couch. Although I was now wearing sensible low heels, I seriously

doubted I could stand up in front

of a class for three full hours – the total duration of

the two classes I would be teaching back to back. But a friend who is a teacher had assured me that having kids there energized you. I found a central spot in which

to station myself at the front of the room. We would see.  Chief among the many things I had fretted about in

the preceding weeks was that I would be flummoxed while trying to advance the Google Slides presentation I’d prepared

while I continued to talk. But a savvy teacher’s

aide had been dispatched for this high-tech purpose. All I’d have to say was “Next slide!”

My wish was her command. My other looming concern was that my lecture would

not be interactive enough. Hence the special prop I had brought, which I now slipped surreptitiously out of my bag.

Most of these premed and pre-dental students were presumably science majors. Many spoke English as a second

language, having grown up in distant places, including Puerto Rico, Ghana, and Nigeria. I worried that they would be intimidated about needing to write. So I had come

up with a ploy that I hoped would help boost their confidence.  There was no way they could go wrong, I told them, since

the subject about which they would be writing was one on which they happened to be the world’s leading expert. Themselves. Then I asked for a volunteer. One hand immediately shot up. It belonged to a young man sitting toward the front. “What’s your name?” I asked. I whispered this under my breath, hoping

to continue with the presentation seamlessly, but the boy’s accent proved to be so heavy that I had to ask him to repeat

it three times. He finally resorted to pulling out his wallet

and showing me his student ID. And even then I did a double-take, thinking I had it wrong.

“Silverberg?” I asked

a little incredulously. Who knew?

Although you never know for sure, I must admit that he certainly didn’t look Jewish.

Silverberg, however, was his first name, not his last. Could that be

a popular boy’s name where he had grown up?  Whatever the case, I proffered my special prop –

my daughter’s satin cap with a golden tassel from her high school

graduation – and asked him to slip it on. “Ladies and

gentlemen,” I announced, drawing out the words with a typical circus ringmaster’s basso profundo, “introducing the world’s leading

expert on Silverberg: Silverberg!” He needed no prodding to take

a bow. Everyone applauded wildly… and laughed. The cheering continued

as Silverberg returned to his seat. I cheered silently inside. Maybe this was going to be OK, after all.  To keep things light and also loosen the

group up, I had prepared a couple of quick writing

exercises “to warm up your writing muscles,” I explained. “Next

slide, please,” I told my trusty TA. She

forwarded my presentation to a photo of a juicy cheeseburger on a bun. “Here’s the beef. What’s the story?” I asked the class.

Without any further prompting, everyone whipped out paper and pens and began to

write. I gave them only a few minutes, but when I asked for volunteers to share what they had written, I was surprised to discover how much they had managed to jot down.  One boy wrote a melodramatic tale of woe told from the point of view of a cow. Another,

who was evidently from Maryland, crafted a story about a crab cake instead. All were more creative than I had expected. Maybe this was going to be OK. At the astute suggestion of the neighbor before whom I’d practiced the night before, I had chosen to divide my allotted 90 minutes into three equal parts. Before

I knew it, I had gotten through the first segment, on basic writing skills, and moved on to the half-hour on specific guidelines for the essays they would write.

All that remained was to read my selection of actual essays from successful dental students aloud. After each, I solicited comments. What did you like about this one? What didn’t you like? This stimulated a bit of debate, led by the stalwart Silverberg. I stopped five minutes before the end to take questions. But there weren’t any. After all my anxiety about not fitting in all of my material,

I’d finished five minutes early. I had been extremely

anxious when I’d learned that there would be only 15 minutes between the first 90-minute class

that I would teach and the next. Wouldn’t I need to take a break and rest up, or at the very least go to the restroom? But on the contrary, I now felt so energized that it seemed to take an eternity for the next group to wander in. I couldn’t wait for the next class to begin.

These were the medical students, who proved to be equally enthusiastic about the snacks and even more forthcoming

and contentious when it came to class participation. By the time I had

gotten to reading the actual essays aloud, they became near savages, tearing apart each as if with the precision of a surgeon’s

scalpel. Their chief complaint in each case was that they didn’t really believe the writer genuinely wanted to be a doctor.

“Guys,” I

finally said, chiming in over their chorus of derision, “think of all of the effort you have gone to as premeds

and all of the effort that awaits you in med school. Who in their right mind would endure all of that if they didn’t really want to be a doctor?” That seemed to stop the onslaught of disdain and before I knew it my second 90 minutes were

already up, too, and I had managed to finish yet another class, this time ending right on the dot.

I was astonished at how many students stopped on their way out to thank me and say how interesting or helpful

the session had been. But my favorite comment was one that I merely overheard. As

they were walking out, one girl exclaimed to another, “Wow! That didn’t

just make me think about my essay. It made me think about my whole life!”

I had been so worried that I wouldn’t be able to stand up for the full three

hours. But my teacher friend had been right. Having students to teach didn’t just energize you. I had found the whole

experience so exhilarating that I couldn’t get to sleep that night. I

had given the students 10 days to write their essays because I wanted them to have time to think about them, work on them,

and, like any good writer, revise them. And to my

delight, with only a few exceptions, nearly everyone made the deadline.  The good news, I discovered, was that nearly everyone also had “gotten it” and taken my advice to heart. The essays were brimming with colorful detail, in some cases too much of it. There are strict limitations about essay length. Dental schools will accept only 4,500 characters

including spaces (just over a page or so long). Med

schools allow only 5,300. One med school essay I received was nearly 12,000 characters

long – over twice the limit. I had my work cut out for me just cutting it down to size. But that was the least of my challenges. Silverberg, it turned out, wasn’t the only participant with an unfamiliar moniker. Rather, he was among the few whose names I knew how to pronounce. Others had first names including Akosua, Aaliyah, Tumani, Shanicka, Noheli, Kodilichi, and Antoneal. But the issue at hand, I soon learned, was not my ability to say things, but

theirs. Although almost everyone had wonderful stories to tell, many had a great deal of trouble telling them. They didn’t just need an editor. Some almost needed an interpreter. “Through

my desire to become a doctor, I participated in experiences that helped shape some of my competency in humanity, especially

with the underserved and low-income families,” one girl wrote. I decided to recast the phrase “helped shape some of my competency in humanity,”

to be simply “helped shape my compassion

for people.” “That’s what I meant!” she would later tell me.

Almost everyone had grappled with

more than their share of difficult obstacles – being raised in poverty by

single mothers, needing to work their way through school,or being obliged to care for their younger siblings or family members who were seriously ill.

One girl began her essay by noting that she had become a mother at the age of 13. I was shocked, until, reading further, I realized what she meant and inserted a key additional word. She had functionally become a mother at age 13, following an accident that befell her father

and the abrupt departure of her stepmother, leaving her to care for two baby brothers, then an ailing grandmother. Throughout

middle school and high school, she’d been obliged

to handle their care and feeding and

all the other household responsibilities, yet still had managed to finish high school at the top of her

class. Although well-meaning people had kept urging her to go pursue her own

lifelong dream, she had remained close

to home during college to continue assisting her family. Now, at long last, with her younger

siblings about to enter high school, she felt that she could finally apply to med school, confident that they were old enough to manage on their own, free of the pressures she had faced. Yet something had occurred to her as she had proudly cheered their names at their middle school graduation: They were now the same age that she had been when she had (functionally) become a mother. If she didn’t deserve to get into medical school, who

did? By the time I had finished editing her words, they read like a beautiful novella. A well-written, beautiful, gripping novel. Which brings me to a rather gripping point. You might question

the ethics of my providing such a high degree of

help to these students. I questioned this quite a

bit myself. Perhaps it wasn’t fair to raise the level of their writing quite

so much – and had they been aspiring to become lawyers, English professors, or other careers that required them to write articulately, that might be true. But as a friend aptly pointed out, in this case maybe I was just leveling the playing field. Most

middle-class kids had parents or friends of the family to review their essays. Some even

had the means to hire professional consultants

to do what I had done at considerable expense. Most of these students were the first members

of their families to attend college, let alone grad school.

They needed – and deserved – all the outside help they could get.

And in the end, this venture didn’t just aim to help a handful of students achieve their ambitions. It was meant to address an insidious ill that plagues our

entire society.  Grave disparities exist in the level of health care available to people of means and those who are members of minority groups and/or economically disadvantaged. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, racial and ethnic minorities made up 36.6 percent of the population

in 2012 – a number that has presumably increased since then. Yet according to a survey conducted by the Center to Study Health System

Change, only 3.8 percent of physicians were African-American and 5.3 percent were Hispanic.

Studies show that health-care professionals who are Latino, African-American, and Native American are

more likely than others to treat minority and indigent

populations. A 2010 survey of more than 7,000 U.S. patients conducted by Harvard University found that minority doctors care for some 70 percent of non-English-speaking

patients. It also indicated that Asian, Hispanic,and African-American patients were up to

26 times more likely to be cared for by a doctor of the same race. Programs like UConn’s HCOP are needed to help reverse these troubling trends by attracting more minority members to practice medicine and dentistry. And they do clearly help. Since 1996, HCOP has

sent more than 400 participants to med school, dental school, graduate school, and other health professional programs. In the Jewish spirit of Tikkun Olam ("Repair the World"),

I was proud to be part of it. So I gave it my best shot. And my best shot took quite a lot. Never mind that I had agreed to spend only 20 minutes editing each essay and would only be paid for

that amount of time. Some of the personal statements took me as much as two hours to edit. On average, they required over an

hour apiece.

And the revisions that I did following my meetings with each student took another 30 minutes each, on average, rather than the 10 minutes I’d agreed to

spend on them. As for the 15 minutes I was allotted to meet one-on-one with each student, that also proved to be something of a joke. And that joke was mostly on me. Yes, in a few cases, that amount of time proved to be adequate.

But I had been scheduled to conduct these meetings one after another, without a break, for three days straight.

And in each case I soon found myself running

increasingly behind schedule. Most of the students

were understanding and accommodating,

but it was embarrassing to keep them waiting. I often would be forced to say that we would have to continue

conferring by email. But it was so much more

effective to do it in person. Oh, well.

The upshot was that I was up editing until 2 a.m. every night for weeks… except for the days that I met

with the kids. On those nights, I was up preparing until 3 a.m. Yet in the end, every single one of them had a very strong essay ready to submit. And by the end, I felt myself growing deeply attached

to them… and very proud of

them. I also discovered that all my hard

work had not gone unnoticed – by the students themselves, at least. “I have read the essay,” wrote Shanicka after receiving her final version, “and it is a huge canyon

between where I started and where it is now. I love it! I would like to thank you for taking the time to not only critique my essay, but getting to know what I wanted to express and translating that into a smooth personal

statement.” Another, named Kodi, was similarly grateful. “Thank you

so much for your help!” she wrote. “I really enjoyed working with you and love the corrections you made!”

She also vowed to let me know how she faired with her

applications, something that I had requested

of every participant when I had written

to congratulate and thank each one.  I was thrilled to be invited to the graduation ceremonies

on the very last day. When I entered Keller auditorium, I lit up to see my students sitting together

up front. But the most thrilling part was that many of them lit up to see me and began to call my name. There

was Silverberg in a bright pink shirt with an even brighter (pre-dent’s) smile.  There, also, was Adrian, a good-natured young man who had written that his greatest motivation to become a

dentist had been being told that he could not; when he had divulged his ambition to his high school guidance counselor, the

man had advised him to aim for nursing instead. Adrian had taken to emailing me round the

clock as I'd patiently coached him through at least half a dozen drafts... and consistently

assured him that he could do it. When I told the kids once again

how well they had each done with their essays, Adrian piped up eagerly that this might be true, but that I had been “the

secret sauce.” “Can I put that on my résumé?”

I asked him, earning me another huge smile. Better yet, I could get business cards that stated just my name

with that phrase beneath – “the secret sauce.”  Afterwards, I took photos as the group huddled together onstage, and an incredibly poised

and impressive girl named Christiane seemed

more than happy to pose with me. It was with

mixed emotions that I drove home afterwards. I was so proud of them. And glad I had gotten to do it. But

I was also a little relieved to be returning to my real nice Jewish life. For that reason, although I was wistful to see my duties there end for the year, I was also a little

unnerved when over the coming days many of the participants

continued to email me their personal statements, which

they had continued to fiddle with, or to send me

supplemental essays from their applications to revise as well.  Normally, I’m just a mom who can’t say no. So in a few cases, I quickly caved in. But I’ve begun summoning the nerve to reply apologetically that my work there is done for the year. After all, it’s now mid-August and I have yet to even see the ocean once

this year. TV ads are already advertising

back-to-school merchandise, and I just got out of school.  So before autumn leaves start to fall, I am about to join my husband on a much-needed summer vacation.

I may be a mom who can’t say no, but I am saying no to everything else, including writing my blog next week. So please don’t look for me here. Or

anywhere near a computer. I’m trading in my uncharacteristically conservative

togs for flipflops and a tankini. Next slide,

please, and it better be a picture of the beach.

See you in a couple of weeks! Love,

Nice Jewish Mom

a.k.a. The Secret Sauce

Friday, August 7, 2015

A

Word From The Weiss  The word I would use is beshert. Yes, you normally employ that

Yiddish expression only when you’re

talking about love. That’s what I was inclined to call it when I first met my husband, way back when. It also seemed to

apply when we first laid eyes on our dog, Latke (or more precisely when she first waddled over to my husband and laid her head on him).  It’s just not a term

you normally employ when you're talking about employment. But there’s only one

way to describe how I got my job this summer. I think

it was beshert. Meant to

be. It all started when I was sitting in my doctor’s office last April.

My daughter had come home for Passover all the way from Hong Kong and said she wasn’t feeling well. Allegra hadn’t been to a real doctor (i.e., a Jewish one) since leaving for Asia nearly a year before. So as soon as our family seders were over, I arranged for

her to see mine. We were sitting in the waiting room when a friend of mine walked in. I had known Nancy ever since joining my book group, the Shayna Maidels, more than a decade ago. Being a nice Jewish book group,

we discuss a lot more in our book group than books. We talk about our childhoods. We talk about our children. Those who already have grandchildren talk a whole lot about them. But up

until that moment, it somehow had never once come up in conversation that Nancy and I go to the same female doctor.   Although she already had just seen the doctor, she sat down with us in the waiting room and began to schmooze at length. And after she had finally finished bidding us a 20-minute (i.e. Jewish) goodbye, she walked right back in again because

something else had just occurred to her. A few days earlier, she had been offered a job. She’d turned it down because it wasn’t exactly within her wheelhouse, as they say. But it had suddenly crossed her mind that maybe I’d want this because it was right within mine. For the past

19 years, the University of Connecticut Health Center has offered a series

of special courses in the summer called

the Health Career Opportunity Programs. Geared toward students ranging from middle school through post-college, HCOP aims

to increase diversity in the health care field by helping young people from various backgrounds underrepresented in the profession get into medical and dental schools.  For 17 of those years, Nancy, who is a speech

pathologist, had been helping the participants with their interviewing and presentation skills. The program's directors had apparently just come to the conclusion that the college students also needed help writing personal

essays for their medical and dental school applications. This was

not up Nancy’s alley. But

yes, it was right up mine. We

continued to confer over the next few days, and shortly after Nancy arranged for me to have an interview at UConn Health Center. I spent days before it rehearsing in my mind

how I would convince them to hire me. After more than three decades as a journalist, I had been

writing a weekly personal blog for nearly five years, meaning that I had penned over 250 personal essays in this space alone. As for teaching experience, I had guest-lectured on journalism at the

college level, as well as worked for two years as the faculty adviser to the student

newspaper at a local high school. If there was one thing that gig had taught me, it was how to edit young people's writing

so carefully that I could clarify what they were trying to say without their noticing that I had actually changed anything. While there, I had also offered to help many of the seniors on staff with the personal

essays for their college applications (something that I’d already done for

my own children and many of their friends).

Having been self-employed as a free-lance writer for the past 20 years, I couldn’t imagine whom I would

ask if they requested professional references. So I brought along to the interview something that I thought would not just suffice, but might be even better: a thank-you note from one of those high school

newspaper staffers I had helped.  “Thank you for the multiple readings of the last-minute emails I sent to you, the

chats about ‘where I was going with this,’

the editing I could not see, the cutting I could not do, and the finished product that I submitted on Nov. 15th,” it read in part. “Your comments and insights helped me produce a college essay that I have confidence

in… With your help, I gave those colleges a piece of my soul, and whether they accept

me or deny me, I can at least be sure that it was not because of that essay.”

I went to the interview prepared to

tell them that the “piece of her soul”

this girl had submitted had been so compelling that she’d gotten into every

college to which she had applied. But it turned out there was no need. Thanks to

Nancy’s endorsement, no one was questioning my qualifications. All they really wanted to know was how I would

do it. Good question, and one to which I’d given

little thought. So I made it up on the spot. The students were so busy taking science courses and practice exams, I was

told, that they only had time for me to teach one 90-minute class to each group. After that,I could meet with them one-on-one for only 15 minutes apiece. Ideally, I would have wanted much more time. But I agreed to work within those

parameters by having the students email me their essays after I’d taught the initial class. That way, I could edit them on my own time and make our 15 minutes

together as productive as possible.  Here was the sticky part: I was obliged to estimate in advance how long it would

take me to correct each essay, and I would only be paid for that amount of time. The students I would be working with were all presumably science majors, and many were from impoverished

backgrounds. They might not have strong writing skills. But the program’s budget was limited, and I didn’t want to price myself out

of their range.  So even though I feared it would take a whole hour to work on each of the 34 students’ essays, the proposal I submitted said I would spend only 20 minutes editing each. Then,

after meeting one-on-on, I would devote 10

minutes more to reading the revised versions they’d send me. I knew these numbers were unrealistic. OK, let’s be honest. They were probably insane. But I really wanted to do this job. And it was such a good cause.

Although I have been writing this blog every week for five years,

I haven’t held a regular job (i.e., one I couldn't do in my pajamas) for some time. The day of my interview, my husband bought me flowers.

A week later, those flowers had long died and I hadn’t heard back. But

at long last, I received the final word.  I had it! I got the job!

So my husband bought me flowers again. And then

the actual work commenced. Although the program didn’t start until late June, I had to spend weeks preparing. How would I teach these science kids to write a persuasive essay in only 90 minutes? How would I make those

90 minutes interesting and interactive? Also – and I shudder to admit this – things had become a whole lot more high-tech since I’d last

taught a class. How would I make a PowerPoint? I also needed to bone up on precisely what medical and dental schools essays entailed. I spent weeks pouring through books with titles like Essays That Will Get You into Medical School, How to Write a Winning Personal Statement for Graduate and Professional School, and Medical School Essays That Made

a Difference. I also scoured the Internet for guidelines, information, and actual essays that had made a difference.  And when I couldn’t find quite enough top-notch samples from successful

dental school applicants, I wrote to a few leading schools for help. Only the head of admissions at Harvard School of Dental Medicine ever responded. Rules about confidentiality prevented her from

supplying any actual essays. But she did offer some sage advice. “I

have read nearly 10,000 essays in my years at Harvard,” she wrote, “and I would say that most applicants make the tragic mistake of taking a formulaic approach, such as: my orthodontic experience, my childhood injury, I loved/hated the dentist

as a child, the homeless patient I met at a dental clinic, my experience on a medical/dental mission trip in another country

that made me aware of health care disparities. “This last

one is a challenge for me,” she continued, “because there is so much need for health care in this country; no need to go outside of the U.S. to learn this.” But the ultimate challenge for most applicants remained tackling the blank page itself. “I

usually advise students to write about themselves, what makes them stand out

as an applicant, and why they are interested in caring for human beings,”

she said.  My own dentist, Dr. William Lavine, expressed similar sentiments. “I was on the admissions committee for a while in the 1970's when I was a full-time faculty

member at UConn,” he wrote back. “At that time, I was looking for some expression

of compassion – sensitivity to the needs of people – not just an

avenue to a secure income, although that is a realistic consideration. I always

asked myself, ‘Does this person have a heart?’” Although all of the books I read echoed this basic theme of

needing to demonstrate a desire to help others, they also made it clear that this alone would not suffice. An article about applying

to dental school that I found online made this very clear. “Although there is no formula for a winning statement, there

are some tired themes to avoid,” wrote a fellow named Don Osborne. “First, don’t just say you ‘want

to help people.’ It is assumed that every potential dentist wishes to help his or her patients. Admissions officers have read hundreds of ‘I

want to help people’ essays.”

What they wanted instead was

a narrative that revealed why the writer wished to be

a doctor or dentist and then went on to describe key experiences, such as volunteering, research,

and shadowing health care professionals, that

made them eminently qualified. But it was important

to avoid simply rehashing one's résumé. Other areas of the application

would give these details and concentrate

on “Just the facts, Ma’am,” providing

numerical attributes like grade point averages and standardized test scores. The

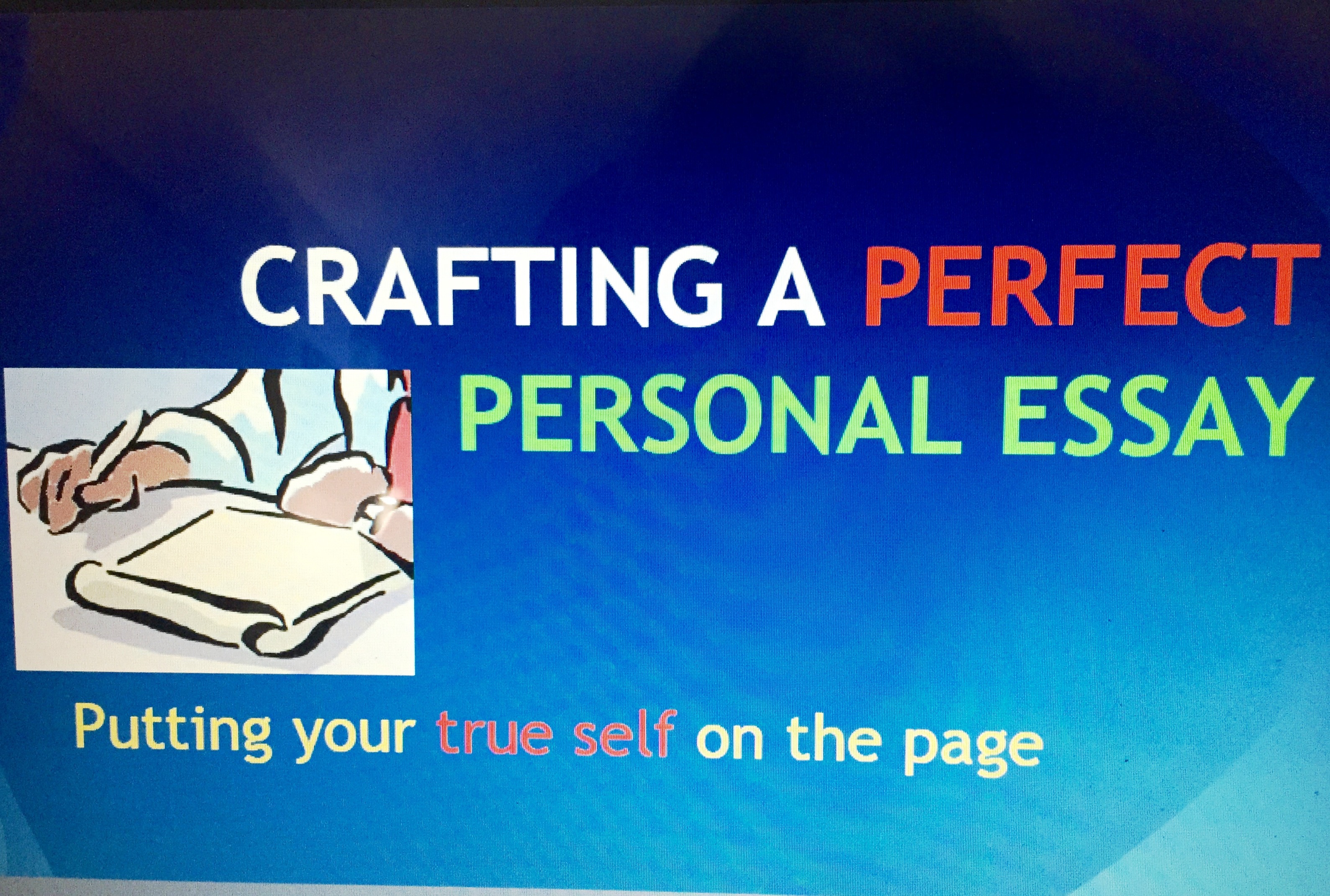

personal statement was one of the only opportunities students had to put a face on their applications and demonstrate real character and genuine commitment. With that in mind, I spent weeks planning my lecture

and compiling more than 20 pages of handouts to give each group. Then I dared to attempt the dreaded PowerPoint.  My daughter’s boyfriend, JP, a coding teacher and computer

whiz, recommended using Google Slides instead. He assured me that this program was self-explanatory. And guess what? He was right. Along with writing this weekly blog, I man (or woman) the entire Art Department at NiceJewishMom.com. I take all the photos and find or create all of the graphics as well. So designing slides to go with my syllabus was pretty much a snap. The hard part was boiling down the concept of How to Write into a quick lecture. Obviously,

it was too late to begin explaining the basics of grammar and punctuation. Those who had yet to master semicolons and the subjunctive weren’t going to get them from

me.  Instead, I would begin by providing simple ways to make your writing much better. "Crafting the Perfect Personal Essay," I called it. "Putting Your True Self

on the Page." It occurred to me that my students would be spending

most of their other time trying to get their board scores upby studying for tests, followed

by taking practice tests. I wanted my class to be the fun part, rather than another

source of pressure.  “This is not a test,” I wrote. “When you write a personal essay, there

are no RIGHT answers. There are only two questions: Who are you and what do you have to say?”

As intimidating as the blank page might seem to these students (and most other

people), in this case it was important for them to

keep one very reassuring thing in mind. You couldn’t really go wrong with these essays, I would say, because the subject you

were writing about was one on which you happened

to be the world’s leading expert.  You.

But whatever

they had to say on this subject, the most important thing

was to write in their natural voices. This was not the time to pull out all the big SAT words they knew. “Say it – don’t convey it,” is how one of my Google Slides put it.

That was the first of Five Easy Fixes I’d give that are“shortcuts to sharper writing.”  “Write just the way you speak,”

I would explain. Too many people think that when

they write, it's necessary to adopt a stiff, formal tone, like in a textbook. On the contrary, “Good writing does not have to sound like ‘Writing’

with a capital W,’ I would tell them. Rather,

“Use your own voice – you know. The one you use to tell a story to a friend.” Or your mother.  Also crucial to making writing more engaging was to supply a wealth of detail. “Be as specific as possible,” I wrote. “Specific details make writing speak to you. They make your words seem like

they almost fly off the page.” To help demonstrate that, I chose an interesting story

from The New York Times and

supplied two versions of its opening paragraph. Both included the

same basic facts, but in the first version I deliberately removed nearly all

of the specific details. “Mean bosses

made my father miserable,” it began. “I

recall walking into a hospital room to see my father lying there looking really ill. What put him there? I believe it was

work-related stress. He had two bosses who were really mean.” The

second, the one the paper had actually printed, was brimming with rich detail.  “Mean bosses could have killed my father,”

it began. “I vividly recall walking into a hospital room outside of Cleveland to see my strong,

athletic dad lying with electrodes strapped to his bare chest. What put him there? I believe it was work-related stress. For

years he endured two uncivil bosses.” I would ask the students which

of the two made them really see a picture, and which one engaged them more and made them care about the people in the story. Of course, the most effective details to include when you were writing anything were ones that engaged any of the five senses – sight, hearing, smell,

taste and touch.  “A good piece of art makes you really want to go to the place that you see,”

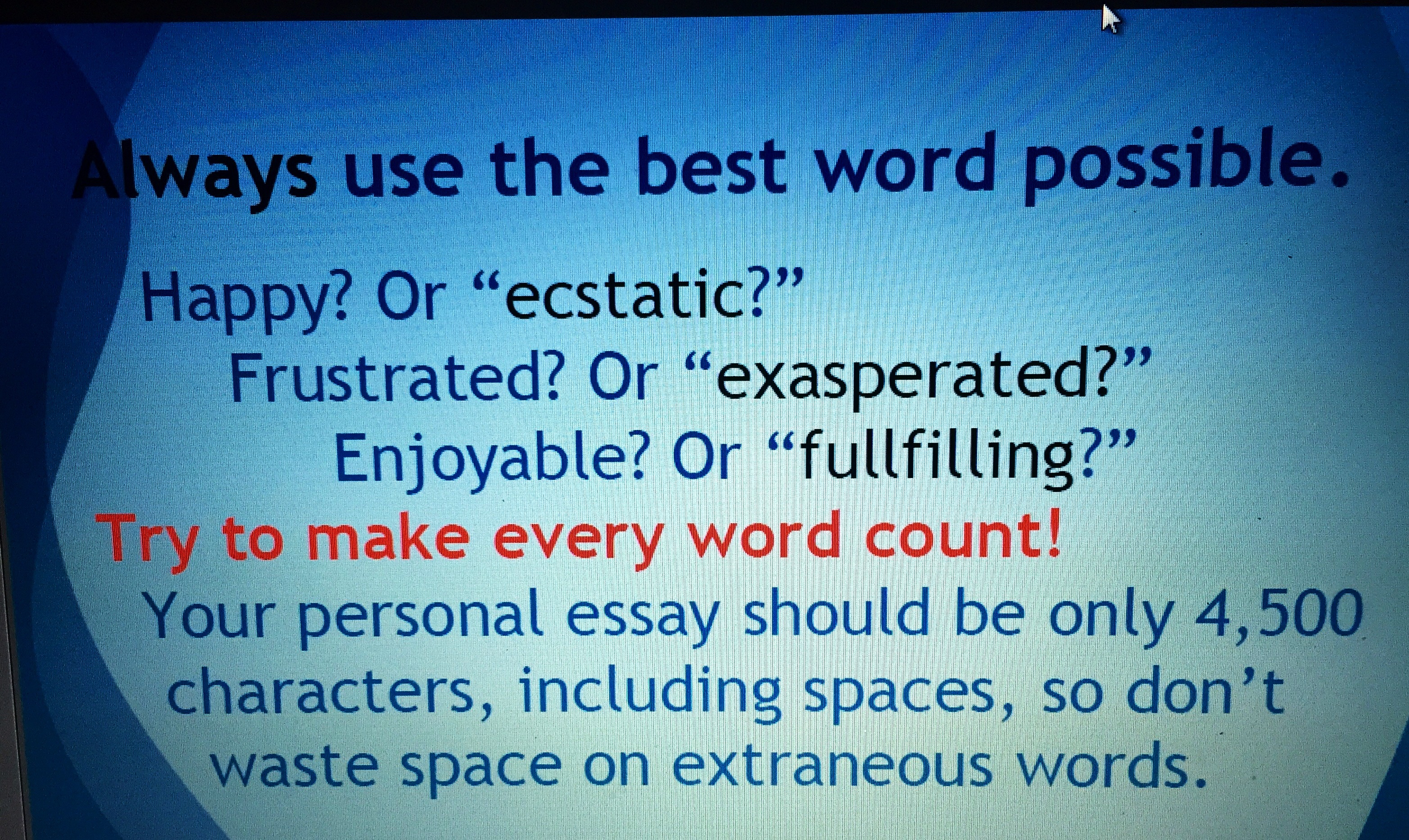

I would explain. “A good piece of writing makes you care and feel like you are actually there.” Paying attention to word choice was another quick fix, especially in this case. Their personal statements had a strict space limit, so they needed to make every word count.  “Always

use the best word possible,” I would say. “Happy

or ecstatic?” “Frustrated or exasperated?”“Enjoyable or fulfilling?” A good writer thought hard about nearly every word and found one that expressed precisely what he or she wanted to say. A good writer

also makes sure to say something to grab the reader’s attention right away. In today’s busy world, you

only have a few seconds or sentences to hook someone

before they lose interest and move onto something else. This was especially true for these

essays. Admissions officers would be reading hundreds of them. The kids needed to find a way to win them over at onceand make them want to keep reading.  Good opening sentences, I would explain, are often short and snappy (or, on the contrary, may be long, detailed, and able to draw the reader into the story right away). They also instantly

set the tone for the story and may raise questions that you want answered. But the best of them hit you right between the

eyes by saying something that is surprising, shocking or in some other way unexpected.

With that in mind, I decided to offer a few of the best leads in literature

ever written. Of course, these kids were just writing the personal essays for their school applications. No one expected

them to be Shakespeare. But why not set the bar a little high anyway?  Herman Melville’s epic novel, Moby

Dick, had begun with just three words, but they were well-chosen ones that were eminently

conversational and sucked you in at once: “Call me Ishmael.” Whether

or not they have ever actually read the book, who among us is not familiar with the memorable opening gambit to Charles’ Dickens classic, A Tale of Two Cities? “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…” And although he may be best known for his lengthy masterpiece War and Peace, 19th century Russian writer Leo Tolstoy proved

to be the master of the opening line when he began his tragic love story Anna Karenina like this: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is

unhappy in its own way.” (Face it – happy families

are also rather boring to read about. Unhappiness,

on the other hand? Tell me more!)  Of course, my students would not be expected to write novels or fiction of any sort. This was

not the time to get too creative or experimental. What was it the time to do? Tell them who you are. And who you want to be. Be focused. Be clear. Be specific. Be honest. But most of all… BE YOURSELF!

There. I was done at last with lecture and my PowerPoint… er, Google Slides.  And that’s when the terror set in. It had been a while since I had taught a class of any kind. What if the kids didn’t

like my presentation and just sat there looking distracted and bored? What

if I ran out of material long before my 90 minutes were up? More

likely, what if the class ended and I hadn’t gotten through half of my lecture? There was no chance in this case to

pick it up where we had left off the following week. There was no following week. To get the timing right, I kept

practicing my spiel in front of a pretend audience. Sometimes I would practice it instead in front of the dog. Talk about looking

bored. When she paid attention at all, she did not appear enthralled.  The day before my class, while walking the dog (so she could relieve herself and also her boredom)

I ran into a neighbor. I had told her previously about my summer job and admitted

now how anxious I was. Never mind that she was seriously ill and undergoing chemotherapy. She invited me to come over that

evening and give my lecture to her. I declined, not wanting to impose, but she insisted that she didn't mind at all and truly wanted to hear it. So I packed up my computer and went. For the first

time, I was able to deliver it in front of someone who seemed thoroughly engaged.  She paid rapt attention. She

nodded with approval. Unlike Latke, she

even laughed at my feeble jokes. Then again, I was able to see when at times her attention

began to wander. Those were sections that I could cut. I went back home brimming with true confidence where

the trepidation had been. “I can do this,” I thought. “I’m ready!” And in the

end, this wasn't about my being good. It was about my doing good.

Besides, this job wasn’t just right up my alley. It was beshert.

Next week: How it went.

|